Publications & presentations

Introduction

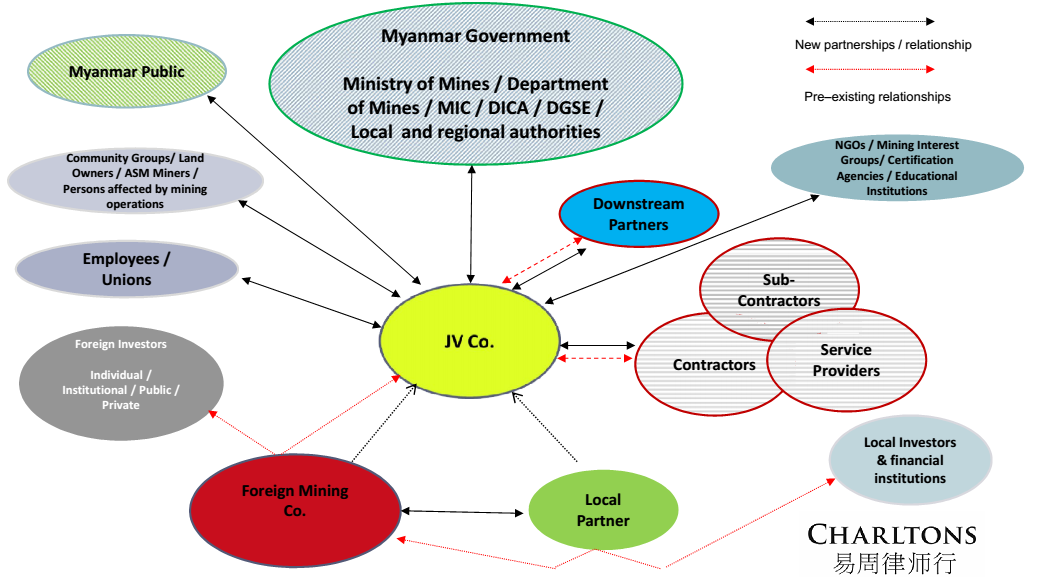

- The 2015 Mines Law and the 2012 Foreign investment law (FIL) together with other legislation, dictates the number and the nature of partnerships foreign mining companies must develop when investing in Myanmar

- Relationships can broadly be described as being either ‘mandatory’ or ‘voluntary’, e.g.:-

- Participatory relationship with the Myanmar Government (Mandatory)

- Relationship with local partner (Mandatory – foreign company must select a local partner from list of pre-approved local companies)

- Employees (Mandatory – FIL applies to employment of local workers)

- Local contractors and downstream operators (Voluntary – but limited choice, for example most possessing facilities are Government owned )

- NGOs / Mining Interest Groups/ Certification Agencies (Voluntary – but the Government regulates the activities of such groups in Myanmar)

- Relationship with local communities – (Mandatory and Voluntary – cooperation with locals necessary to produce EIA, SIA and feasibility studies; but mining companies to decide what voluntary initiatives it will adopt to help it develop its relations with local communities)

- Downstream partners (Voluntary – but prohibition on exportation of crude ore means mining producers must process locally)

- In Myanmar foreign mining companies will also need to develop partnerships to fill capacity gaps which would normally be filled by third party sector participants

Key Relationships and Partnerships

Key Partnerships

- Myanmar Government

- Local Partner

- Contractors, Sub-Contractors, Service Providers

- Downstream Partners and Off-takers

- Community Groups and Persons affected by mining operations

- Employees

- NGOs, Mining Interest Groups, Certification Agencies and Educational Groups

- Myanmar Public

- Overseas Investors, Financial Institutions and Capital Raising Platforms and Exchanges

- Local Investors and Financial Institutions

2015 Myanmar Mines Law (2015 Mines Law)

- 2012 – Myanmar Government announced intention to amend Myanmar’s 1994 Mines Law.

- Delay in enactment has contributed to stall in foreign investment. Myanmar mining FDI was just US$6.26 million in the year ending 31 March 2015. By comparison US$3.22 billion was invested in Myanmar’s oil and gas industry over the same period. *

- Amendments bring Myanmar closer to, but not yet completely in line with, accepted international standards.

- Implementing rules (2016 Mines Rules) to be introduced within 90 days from date of parliamentary approval (24 March 2016). A more complete analysis of Myanmar’s new mining regime will only be possible after the 2016 Mines Rules have been issued.

*Source www.oxfordbusinessgroup.com

Key Amendments – New Activities Permitted

| 1994 Mines Law Prospecting Exploration Subsistence Production Small-scale Production Large-scale Production |

2015 Mines Law sees the addition of new categories – medium scale production and trading. Processing and the production of feasibility studies are incorporated into the expanded definition of ‘Permit’. | → |

2015 Mines Law Prospecting Exploration Subsistence Production Small-scale Production Large-scale Production **Medium-scale Production *Feasibility Study *Processing **Trading **Newly added category *Added via amended definition of ‘Permit’ |

Key Amendments – Foreign investment permitted in medium and small-scale projects

- The 1994 Mines Law, together with Myanmar’s Foreign Investment Law, restricted foreign investment to large-scale mining projects.

- Pursuant to Section 4 (f) of the 2015 Mines Law foreign mining companies will be permitted to form joint ventures with small and medium scale permit holders depending on the ‘quality and quantity’of the mineral deposit in question.

- This amendment only applies to metals and industrial raw materials. Prohibition on foreign participation in gemstone production remains in force.

- Legislation fails to define / describe what is meant by the ‘quality and quantity of the mineral deposit’ but states a supporting geological report is required. Classification of production scale will be made taking into account operating conditions/area, distances,

Key Amendments – Revised Definitions

| Definition | |

| “Mineral” | definition expanded to include metallic minerals extracted from floors of rivers, creeks, ponds and lakes. |

| “Permit” | definition expanded to include feasibility studies, processing and trading |

| “Feasibility Study” | definition added; meaning a study on the commercial viability of a project which should include information on extraction, processing, financial information including anticipated investment, and the environmental and social impact of a project |

| “Trading” | newly added definition; means buying, selling, transport and storage of metallic minerals. (Trading introduced as a ‘Permitted Activity’) |

| “Subsistence Production” | definition expanded to cover basic mechanical mining practices. Change reflects the reality of small scale operations. Old definition described Subsistence Production as ‘production using ordinary hand tools’. |

| “Medium-scale Production” | newly added definition; means medium-scale production from a mineral deposit, which is not a large deposit and which can be carried out for moderate investment and cost or with limited technical know-how and methods |

| “Processing” | definition amended to remove reference to gemstones |

Key Amendments – Permit periods

Definitions of large and small scale production amended to reflect increased permit periods.

| Production Category | Permit Period 1996 Mines Rules | Permit Period 2015 Mines Law |

| Large-scale production | Up to 25 years | Up to 50 years |

| Medium-scale production | – | Up to 15 years |

| Small-scale production | Up to 5 years | Up to 10 years |

No changes to the terms of prospecting permit (1 year), exploration permit (3 years) and subsistence production permit (1 year with 4 x 1 year extensions available). Terms may be amended in the revised Mines Rules.

Key Amendments – Royalty Rates

- Continues as an ad valorem sales based royalty system

- 1994 Mines Law prescribed royalty rate ranges applicable to different categories of minerals. The Ministry of Mines then fixed the applicable rate per mineral within the rate-range.

- 2015 Mines Law prescribes set royalty rates.

- Rate for certain minerals has been set at the lower end of the royalty rate range contained in the 1994 Mines Law i.e. silver – now 4% rather than 4-5%; iron, zinc, lead, antimony, aluminium – now 3% rather than 3-4%.

- However the rate for gold, platinum and uranium has been set at the higher end of the royalty rate range contained in the 1994 Mines Law i.e. 5% rather than 4 – 5%.

- Rate payable on gemstones reduced from 5 – 7.5% to 2%.

- 2015 Mines Law allows local operators to pay tax or royalties in the form of mineral or cash. Foreign invested operations must continue to pay royalties in cash.

- No variation of royalty rates in line with mine size.

Key Amendments – Royalty Rates Comparison*

| 1994 Mines Law | 2015 Mines Law | ||

| Mineral | Royalty Rate Range | Mineral | Royalty Rate Range |

| Gold, platinum uranium, and silver | 4 – 5% | Gold, platinum, uranium | 5% |

| Iron, zinc, copper, lead, tin, tungsten, nickel, antimony, aluminium | 3 – 4% | Silver, copper, tungsten, nickel | 4% |

| Gemstones and jade | 5 – 7.5% | Iron, zinc, lead, antimony, aluminium | 3% |

| Industrial minerals or stone | 1 – 3% | Industrial minerals or gemstones | 2% |

*Select minerals only

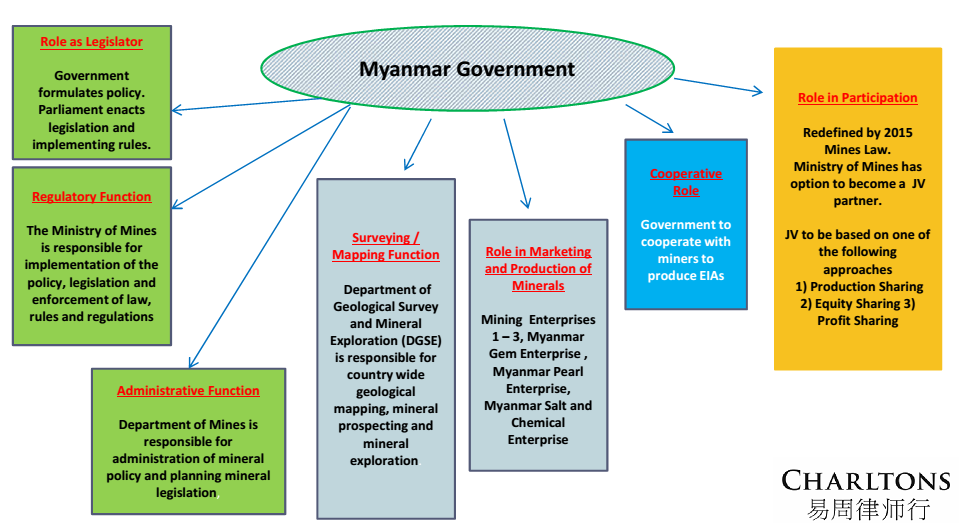

Key Amendments – Government Participation

1994 Mines Law

- Government adopted a Production Sharing System requiring foreign mining companies to cover 100% of project costs and required to surrender up to 30% of output to the Government.

2015 Mines Law

- Pursuant to the new law the Ministry of Mines has option to become a JV partner. JV to be based on one of the following approaches:-

- Production Sharing (Where the Government opts to take a share of production, it must share the costs of producing an EIA)

- Equity Sharing

- Profit Sharing

- Where the Government opts to take equity, the equity share is free ‘carried-interest’ equity.

- The investor-Government split will be based on the investment amount, the type of mineral, the size and quality of the reserve and the cost of production.

Key Amendments – Environmental

- Feasibility study to contain information on a proposed project’s social and environmental impact.

- Operators to establish environmental / social fund for annual maintenance.

- Fund to cover mine closure and site rehabilitation. Questions remain as to legacy rehabilitation.

- Duties of the Chief Inspector expanded to include inspection of the systems/controls an operator puts in place to limit the adverse social and environmental impact of a project.

- Improved clarity on feasibility studies is welcome given their importance in capital raising. Permit system for production of feasibility studies gives the Ministry of Mines additional oversight in the feasibility study production process.

Key Amendments – Decentralisation

- 2015 Mines Law provides for the decentralisation of the application process in respect of permit applications for subsistence and small-scale production.

- State and/or regional authorities are now authorised to process permit.

- Decentralisation initiatives often form part of a broader policy of ‘fomalisation’. Decentralisation amendment does not apply to foreign investors at present.

- “Fomalisation” is pursued by Governments seeking to improve the regulation and management of subsistence and small-scale mining in an attempt to make it a more profitable and economically beneficial sub-sector of an economy.

- Advocates of mining decentralisation argue that regional rather than central Government should be responsible for ensuring compliance with Myanmar mining legislation, overseeing the demarcation of Myanmar mining rights, revenue collection, the processing of mining rights applications, monitoring production, providing technical support to miners and combatting illegal mining.

- The distribution of Myanmar mining revenues is often a contentious issue between regional and central authorities. Decentralisation as part of a broader policy of ‘formalisation’ could help the Myanmar Government’s peace building efforts.

Key Amendments – Guaranteed Right to Production Permit and Offences and Penalties

Guaranteed Right to Production Permit

- Pursuant to Section 11 (a) of the 2015 Mines Law a mining company who undertakes prospecting, exploration and conducts a feasibility study in a permit area is entitled to receive a production permit.

Offences and Penalties

- Sections 25 – 33 of the 2015 Mines Law amends the “Offences and Penalties” set out in Chapter XI of the 1994 Mines law. Fines and prison terms have generally been increased.

Strategic Relationships – 1. The Myanmar Government

- The Government exerts strict control over Myanmar’s mining sector. Through its various Ministries and Departments it is directly involved in almost every aspect of mineral resource development.

- Miners relationship with Government is not a single relationship but rather a multi-faceted relationship with different Government representatives, agencies and departments

- Relationship with Ministry of Mines initiated via a formal introduction process through Myanmar embassy in miner’s home jurisdiction

- Early cooperation with DGSE to obtain resource data

- Myanmar Mining permit applications to be submitted to the Ministry of Mines

- Foreign investment permit application to be made to the Ministry of Mines

- Company and Ministry of Mines to cooperate to produce EIA (costs to be shared if relationship is to be production sharing)

- Local Government assistance required during initial phase of exploration, especially if there are ASM workers or farmers in the mine-site area

- The relationship a foreign mining company develops with the Government is likely to have a material affect on the success or failure of operations.

Developing relations with Government

- Foster individual relationships with Government representatives

- Show goodwill (face to face meetings, information/knowledge sharing, remain cognisant of cultural differences)

- Provide detail of development plans

- Be communicative

- Liaise in respect of public disclosures

- Be patient – huge increase in the workload of Government departments since introduction of political and economic.

- Negotiate in good faith

- Cooperate with the Government in respect of its dealings with local communities and/or other local partners

- Endeavour to understand unique challenges the Government faces i.e. cost of legacy mine site rehabilitation, difficulties in producing reliable resource data.

- Implement effective anti-corruption controls to ensure all company funds can accounted for

- Invite Government participation in development of CSR initiatives and social investment

- Coordinate with Government in respect of security

2. Local Partner

- To operate in Myanmar a foreign miner must establish a joint venture with a local company. The local company’s equity share cannot be less than 20%.

- A primary consideration in the selection of a local partner is the value they can be expected to bring to the JV?

Local Partner – Some Key competencies

- Can provide information on local assets

- Relationships with the Ministry, DGSE, MIC and other Government departments

- Track record in resource development / exploration

- Matches strong local knowledge with technical and geological expertise

- Can manage the hiring of skilled staff locally

- Capable of handling local communications, logistics and security (especially in remote mine areas)

Joint venture parties should know exactly what they wish to derive from their partnership. There should be absolute clarity with regard to the division of responsibilities and rewards.

Due diligence and the protection of interests

- Comprehensive due diligence should be performed

- Searches – corporate / litigation

- Investigate principals

- Ensure no issue re sanctions (SDN list)

- Examine permits etc. (What rights and for how long?)

- Examine other permits i.e. export licence

- Examine corporate filings

- Protections to be embedded in shareholders’ agreement

- Due diligence on Local Co.’s assets and properties if applicable

- Examine commercial agreements

- Due diligence on Intellectual property, if applicable

- Major partner to have protections to be embedded in shareholders’ agreement

- Early agreement as to partners’ representation on the Management Committee

- Certainty in relation to dilution, withdrawal, assignment, default and termination

3. Contractors / Sub-Contractors / Service Providers

- Foreign JV partner may not be familiar with local contractors and service providers. Similarly the local partner may not be familiar with foreign contractors and service providers. Foreign partner can rely on local partner to link them local trusted and legitimate institutions

- JV partners should agree on procurement polices.

- Services required dependent on phase of development

- Local procurement and sub-contracting is more cost effective. Drilling equipment to provide JORC compliant samples (or comparative code)

- Potential for sub-contracting to communities in the vicinity of the mine area.

Indicative range of services

| Exploration | Construction / Extraction | Processing / refining | |

| Equipment | Camping, prospection, drilling and surveying equipment, IT & communications equipment | Drilling, earthworks, construction materials, land clearing equipment | Crushers, conveyor belts, smelters, furnaces, generators |

| Goods and Services | Geochemistry and lab analysis, data processing, cartography, legal, financial and insurance | Explosives, logistics, fuel and gas, chemical and mineral sample analysis | Chemicals / reagents, separators, mills, grinders spare parts |

4. Downstream Partners / Off-takers

- Closer integration of upstream and downstream processes required if Myanmar is to realise it’s resource potential.

- Myanmar’s downstream sector in need of significant investment. Pursuant to 2015 Mines Law foreign participation is now permitted in the processing and trading of ores. Trading includes buying, selling, transport and storage of minerals ore. The exportation of raw ore is prohibited.

- Historically the Government enjoyed a monopoly over downstream activities. 2015 Mines Law amendment means foreign producers in Myanmar are free to develop partnerships with downstream operators.

- Through strong relationships, mining companies can adapt their production processes to meet market demands. Similar cooperation between upstream and downstream operators can drive knowledge, skills and technology transfer

- Improved upstream-downstream linkages proven to reduce waste and benefit the environment

- Prohibition on export of raw ore means producers are obliged to process locally. Processed minerals can be exported depending on the terms and conditions of the production sharing agreement entered into with the Government.

5. Community Groups and Persons Affected by Mining Operations

- Miners should engage with local communities and stakeholders in the vicinity of the mine area from exploration to closure.

- Engagement can help quell local scepticism and opposition and have a positive effect on the perception of mining companies.

- No longer sufficient to limit the negative effects of operations. The positive effects of Myanmar mining should be harnessed.

- Local stakeholders should expect to gain from increased employment opportunities, an improvement in the local skill base, community support, e.g. sponsorships and upgrading of local infrastructure.

- Engagement is essential in the production of Environmental Impact Assessments and Feasibility Studies, which following the enactment of the 2015 Myanmar Mines Law, are required to include an evaluation of the anticipated social and environmental impact of mining operations.

- Communities should have a baseline understanding of the project plan and there should be transparency in respect of project information (including details of annual payments made to the projects environmental and social fund required to be established pursuant to Section 16 of the 2015 Mines Law)

- Miners should engage proactively with artisanal and small scale miners active in a mining area. Mining companies should consider the interconnectedness and mutual-dependence that often exists between ASM operators and local communities.

- Mining companies should engage community groups and local government in trilateral discussions as appropriate.

Example initiatives to develop community relations

- Environmental monitoring and evaluation

- Monitor impact of operations on social structure and the culture of local communities

- Corporate Social Responsibility Programmes (Community health, micro-credit)

- Direct Community Involvement (policies in respect of local employment and use of local subcontractors or service providers)

- Reuse, and recycling of operators resources should be encouraged

- Access to information

- Channels of communication to remain open so that complaints and grievances can be aired

- Direct / Indirect compensation to be paid

6. Employees

- Relationship defined by:-

- Legislation / Government policy

- Employee Unions / Federations

- Mining companies approach to community relations

- NGO’s and international organizations

- Myanmar older labour laws are currently being replaced and/or updated by new legislation

- International Labour Organization, the Confederation of Trade Unions of Myanmar and the Mining Workers Federation of Myanmar active in promoting the interests of the 100,000 or so workers employed in Myanmar’s mining sector

- Foreign mining companies should seek to implement highest standards in respect of health and safety and occupational health. Miners should introduce programs to train and educated unskilled labourers so that there would be future opportunities for advancement within the company.

- Community and employee relations are interlinked. Where feasible foreign miners should seek to employ workers resident in the mine site are. Priority should be given to ASM operators and farmers that had previously owned land included in the mine lease area.

Requirements under the FIL

- Under the FIL, where the foreign investment is in skilled business, a foreign investor is required to employ local citizens as follows:-

Local % of workforce Investment 25% 1 50% 2 75% 3 - Foreign investors only permitted to employ locals in unskilled positions

Employment Law

- 2011 Labour Organisation Law – regulates collective industrial relations including trade unions, employers’ associations, collective actions and lockouts.

- 2012 Settlement of Labour Dispute Law – mandatory conciliation and arbitration mechanisms to settle disputes

- 2013 Minimum Wage Law – employees to be paid national minimum wage as per

- 2013 Employment and Skills Development Law – employer is required to execute an employment contract with employee within 30-days of appointment

7. NGOs, Mining Interest Groups, Certification Agencies, and Educational Institutions

NGOs

- Partnerships with specialised NGOs can enhance project management

- NGOs can co-fund or co-manage CRS initiatives and help monitor impacts of a project

- NGOs can play a key role in developing miner-NGO- community relations

- Role to play in information collection, health education and technical training

Mining Interest Groups

- Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative aiming to improve accountability in the management of revenues from natural resources

- The Asia Foundation, The International Council on Mining and Metals, The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and the World Bank Group have all developed practical recommendations for companies, governments and civil society participants in Myanmar’s mining sector.

Certification Agencies

- Where appropriate miners should seek to develop relationships with Certification Authorities such as those schemes operated by NGOs such as Fairtrade, Fairmined Gold, and the Alliance for Responsible Mining

- An increasing number of international retailers such as Cartier, Tiffany and Co., Wal-Mart, Birks and Mayors have adopted ethical sourcing policies to ensure the products they sell are sourced according to certain recognised standards.

Educational Institutions

- Increased collaboration between Myanmar’s mining sector participants and foreign technical and engineering institutions and universities e.g. University of Exeter’s Camborne School of Mines

- Role to play in information collection, health education and technical training

8. Myanmar Public

- Growing public consciousness of Myanmar mining and energy related projects

- Letpadaung and Myitsone controversies received unprecedented media attention

- The Myanmar public, encouraged by democratic reforms, is willing to express opposition to Government policies

- Miners should consider adopting public and media relations strategies to protect its reputation.

- Miners should remain proactive in respect of communication with stakeholders about the corporate social responsibility programmes it implements

9. Overseas Investors, Financial Institutions and Capital Raising Platforms and Exchanges

- Lack of financing options in Myanmar means mining companies should maintain relationships with overseas investors, financial institutions and capital raising platforms and exchanges

- The approval of the MIC is required for the grant of all forms of security. A mining company operating under the FIL may charge long-term leases subject to MIC approval. However the 2015 Mines Law does not recognise a right to transfer or grant security over Myanmar mining permits

- Other approvals, registrations and filing requirement may apply depending on the type of security being created.

- 2014 – first registration of a secured interest on Myanmar assets for a foreign loan

- There is little precedent on the forms of security that can be taken over shares.

- Question as whether certain foreign exchanges will accept the listing of Myanmar assets.

- It is common for foreign investors to hold shares in Myanmar companies through offshore SPVs so that on a disposal of the investment the foreigner will sell shares in the SPV rather than onshore

10. Domestic Investors and Financial Institutions

- Although the Government continues to implement banking reforms, Myanmar’s financial sector remains the least developed in Southeast Asia. New legislation has been enacted to strengthen the financial system, most notably the Central Bank Law and the Securities Exchange Law.

- Domestic financing difficult in the short term. However sources of domestic finance likely to present themselves in the medium to long-term.

- Foreign banks now licenced to provide limited services in Myanmar. Financing solutions to be provided by foreign banks working in cooperation with local banks.

- Local partners may have access to limited domestic funding

- Too early to say whether the Yangon Stock Exchange will offer viable financing options alternatives

Myanmar Arbitration Law 2016 – The Relationship Challenge of Changing Legislation

- Replaces the 1944 Arbitration Law and gives effect to the New York Convention

- Arbitration Law incorporates most of the UNCITRAL Model Law (UNCITRAL) on International Commercial Arbitration 1985.

- Foreign arbitral awards to be recognised and enforceable in the Myanmar courts.

- The incorporation of UNCITRAL into the Arbitration Law means Myanmar’s courts will now follow internationally recognised rules and procedures familiar to international investors and their professional advisers.

- The adoption of the Arbitration Law does not mean foreign miners will be free to choose foreign arbitration in the Joint Venture Agreements they enter into with the Ministry which is likely to continue to insist on local arbitration.

- Venue for arbitration is now negotiable. Miners can choose to insist on a foreign venue or accept local arbitration.

- Issue likely to be a point of contention between foreign miners and their local partners. A failure to reach agreement or an agreement asserting the will of the major partner over the minor could sour relations. Conversely a satisfactorily negotiated agreement could solidify the partnership.